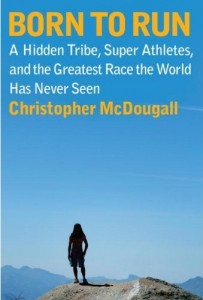

Week four of 2011 had me reading a book that I’d never heard of until the week before. I was hanging with some guys down at a local coffee shop, and my good friend and running partner (partner always sounds so contractual to me) mentioned it and said it was pretty good.

Now, my running partner has a lot of stuff I don’t. A faster 5k time, 8k time, Half Marathon time and Marathon time. He also has better hair, but I don’t hold that against him nearly as much as I do the faster race times. He has a real name, too, but I won’t use it because I don’t want to cross some kind of internet privacy line, and also because I’d rather just call him Jerk, mainly because of all the stuff I mentioned earlier. Well, except the hair.

So, there was no way in double hockey stick land that he was also going to have book knowledge that I didn’t have, too, so as soon as I got home, I fired up the Kindle app on my iMac (which can be downloaded free at the new app store over at Apple’s website) and bought it. Faster than I can run a quarter-mile interval, it was downloaded and I was immediately hooked by a story about ultra runners, the evils of Nike shoes and some people I’d never heard of called the Tarahumara Indians.

Basically, the author hurts his foot, and in his quest to figure out why, he encounters Indians who run hundreds of miles at a time and never get hurt. His quest for answers takes him on a journey that ends with a 50 mile race deep in the Copper Canyons of Mexico. The runners in the race are a pretty amazing mix of people, but the main ones are Scott Jurek, possibly the best ultra runner ever, and some of the fastest Tarahumara Indians in the canyon. The author also runs in the race, but does a good job keeping his race details out of the spotlight, because the race that matters is whether or not Jurek can beat the newly-found Indians (which I will not be revealing in this post).

There is a lot in the book I could have done without, and if you pick it up to read, you might as well know up front that there’s some choice language in it, and some points where it feels like it gets very technical about science, the foot, and whether or not we’ve evolved to be runners. McDougall certainly has a different worldview than I do, and I found myself a number of times answering questions he posed with what seems an obvious answer to me. One section that dealt with our ability to process thought shows what I’m talking about:

Okay, so primitive man upgraded his hardware with a bigger brain—but where did he get the software? Growing a bigger brain is an organic process, but being able to use that brain to project into the future and mentally connect, say, a kite, a key, and a lightning bolt and come up with electrical transference was like a touch of magic. So where did that spark of inspiration come from?

Good question. Simple answer: God.

Of course, that’s not the point of the book, but I did find a clash of worldviews here at times. I also found that the meat of this book was worth spitting some of the bones out. Just know that you may be spitting quite a bit.

Now, here’s some of the meat I found in this great read:

ONE: The hero of the book, for me, was Scott Jurek. He appeared to be the kind of gifted athlete we’d all want to know: gracious, humble, a “man like us.” The author tells of how Jurek would win ultra races and then hop in a sleeping bag at the finish line so that he could congratulate other runners as they came across the line. He’d wait as long as it took in order to see even the last finishers. In a world full of prima-donna athletes (i.e., all the New York Jets), it was really refreshing to find myself pulling for a guy like Jurek to win.

TWO: I was inspired by the community that the runners found. Different people from different cultures and countries came together and learned to appreciate one another. Running was the glue. McDougall wrote about a speech given the night before the race by the American-turned-canyon-dweller that was particularly poignant:

As the American and Tarahumara runners squeezed around the two long tables in Tita’s back garden, Caballo banged on a beer bottle and stood up. I thought he was going to deliver our final race instructions, but he had something else on his mind.

“There’s something wrong with you people,” he began. “Rarámuri don’t like Mexicans. Mexicans don’t like Americans. Americans don’t like anybody. But you’re all here. And you keep doing things you’re not supposed to. I’ve seen Rarámuri helping chabochis cross the river. I’ve watched Mexicans treat Rarámuri like great champions. Look at these gringos, treating people with respect. Normal Mexicans and Americans and Rarámuri don’t act this way.”

As I read that, I couldn’t help but think of the words of Christ as He told His disciples that the unity they shared would be the proof to others of how real their faith was. Reading that speech made me desire a bond like that even more in the community of faith I find myself a part of, and while I know that running might hold our differences at bay for the length of a race, the transforming love and grace of Christ can unify different people forever.

I have no doubt that I was Born to Run after a world like that.